Overview

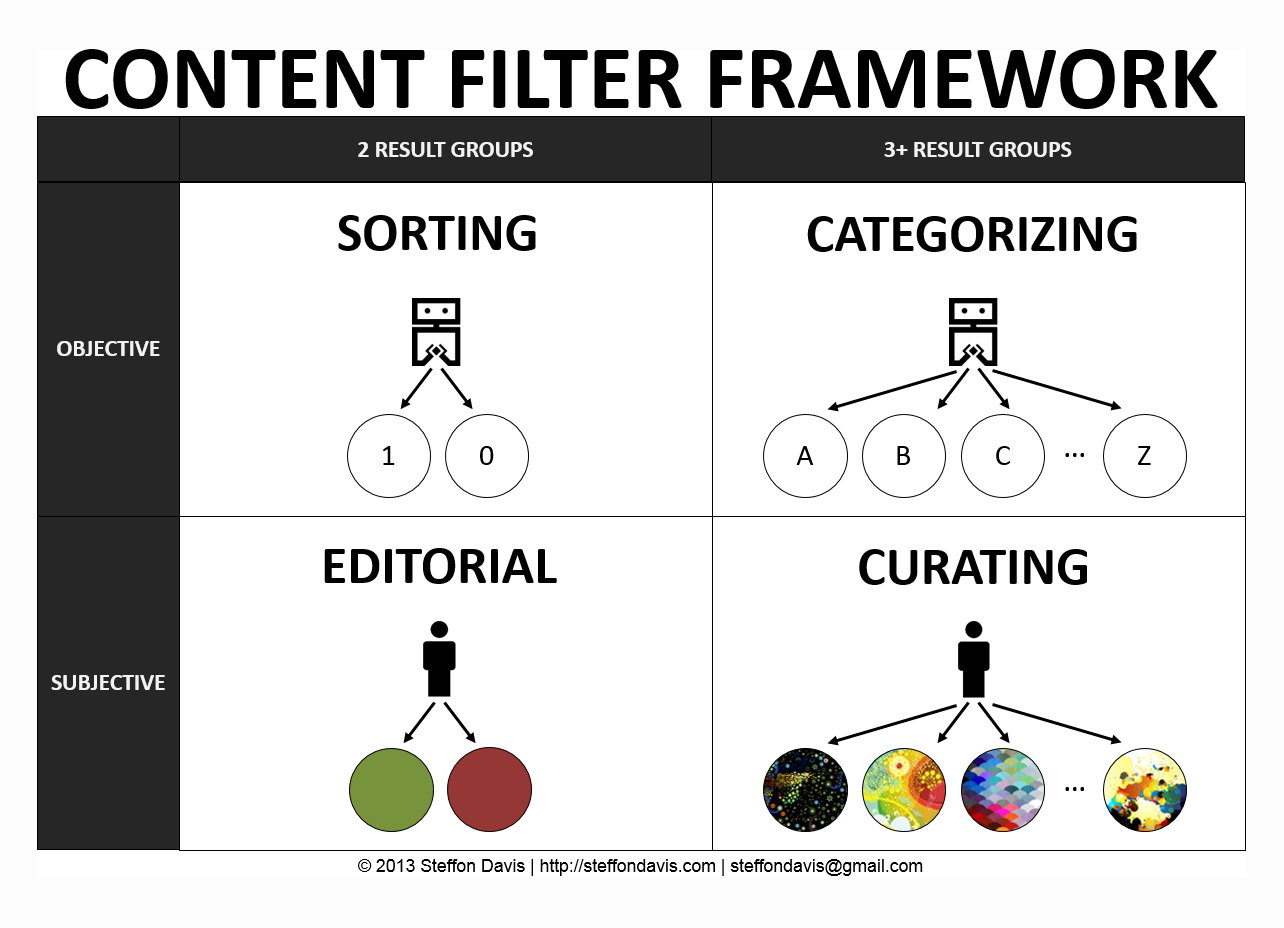

Organization starts in the mind. When we develop a sense of order in our minds and apply it to the world, we organize. Interestingly, our sense of order has predictable attributes. The first pair of attributes describes perspective, which can be subjective or objective. The second pair of attributes determine if we organize into two groups or many groups. A perspective combined with the ability to form groups is called a filter. Our two perspectives—objectivity and subjectivity—when combined with our ability form groups—two groups and many groups—reveal four fundamental filter types: sorting, categorizing, branding, and curating. These four filters are the fundamental ways we organize content and are revealed by The Content Filter Framework.

Sorting

Sorting

You must be “this tall” to ride—no shoes, no service—needle in a haystack—wheat from the chaff; each of these phrases imply sorting. Without the ability to sort we would eat food that is both fresh and rotten, scald ourselves on stove-tops that are both on and off, and sit on park benches with paint that is both wet and dry: We simply couldn’t sort them out.

Sorting is an objective filter that yields 2 groups, like an “in” and an “out” group. For example, you could sort a collection of paintings based on the objective measurement of 20 inches. If a painting’s width is greater than 20 inches it would be “in” while all narrower paintings are “out”. Because the filter criteria is objectively measurable—20 inches—there is a right and wrong way to sort.

Categorizing

Categorizing

A place for everything and everything in its place—Is it vegetable, mineral, or animal? What industry do you work in? These expressions rely on categorizing. Without the ability to categorize, our world would be chaotic as simple concepts like putting things away or alphabetizing cease to function.

Categorizing is an objective filter that yields 3 or more groups of content, akin to the phrase “this, that, and the other thing”. Considering the same paintings as before, you could categorize them based on their medium type, such as “oil” and “acrylic”. If a painting is oil based, it would fall into the “oil” category and if it’s “acrylic” based, it would fall into the “acrylic” category. All other medium types, like watercolor, ink, or pastels could be “other”. Because the filter is objectively measurable—medium type—categorization lends itself to right and wrong answers.

Editorial & Branding

Editorial & Branding

All the news that’s fit to print—family friendly entertainment—the ultimate driving machine; these are examples of editorial & branding. Without them, all the media you consume and every purchase you make may not be of good quality. Imagine buying tomato soup from a bare, silver can with “tomato soup” written on it with a Sharpie. Would it be safe to eat? Would it be tasty? Would one can of soup taste the same as the next? Absent a brand, such as Campbell’s, you can’t be sure what you will get. A brand sets an expectation of quality, like an editor at a newspaper. Soup buyers rely on the Campbell’s brand to only sell soup that meets their standard. And while Campbell’s standards may not meet your own, that would be a subjective difference in opinion.

Editorial & branding is a subjective filter that yields 2 groups of content—an “in” and an “out” group. Because the filter is subjective, it requires the “human element” of emotion, creativity, imagination, and culture, to name a few. For example, consider a museum with the mission to display important paintings, like the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MET). If given the opportunity to display the Mona Lisa on loan, the MET would jump at the chance while, if given the opportunity to display a Power Puff Girls portrait, they may consider it insignificant. If the brand, however, is not the MET, but rather the Cartoon Network (CN), then the CN may arrive at the opposite conclusion and consider the Power Puff Girls portrait a great addition and the Mona Lisa irrelevant. It’s possible for two brands to have an identical mission, to “display important paintings”, but because “important” is subjective, the brand yields different results.

Curating

Curating

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder—one man’s trash is another man’s treasure—that’s not my cup of tea; these phrases rely on the concept of curation. Without curation, we lose the ability to find content interesting, attractive, and likable in different ways. It allows us to avoid a “police state” of preferences where everything is either “good” or “bad”.

Curating is a subjective filter that yields 3 or more groups of content. Like the branding filter, curation is subjective and requires the “human element”. Unlike branding, curation acknowledges that people appreciate content in complex ways. For example, someone may want to collect paintings in meaningful ways. The Mona Lisa may be put into a collection of “classic” paintings while the Power Puff Girls portrait is arranged with “happy” art. One could imagine a collection called “painted women” that includes both the Mona Lisa and the Power Puff Girls, or a collection called “modern art” that includes neither. Existing outside the rigid confines of “good” or “bad”, the curation filter groups content in complex ways that resonate with people. Like our ancestors who collected beautiful, useful, and fashionable shells, so we curate collections in meaningful ways.

Image Credit: the picture of the four buttons on the homepage leading to this article was made by Megan Gouws.